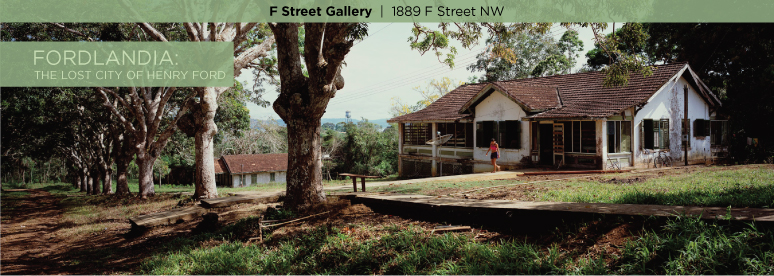

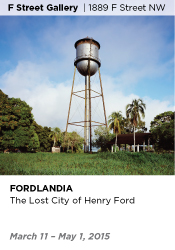

Fordlandia: The Lost City of Henry Ford

Exhibition Page

ONLINE PRESS RELEASE AND OTHER RESOURCES

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

February 25, 2015

Additional images available

CONTACT:

Greg Svitil | T: 202.370.0147

gsvitil@oas.org | AMAmuseum.org

Fordlandia: The Lost City of Henry Ford

On view March 11-May 1, 2015

By appointment only, Mon-Fri from 9am to 5pm

Please call 202-370-0151

Opening Reception: Wednesday, March 11, 2015 at 6pm

(no appointment necessary)

OAS AMA | F STREET GALLERY

Organization of American States

1889 F Street, NW

Washington, DC 20006

AMA | Art Museum of the Americas and the OAS Department of Sustainable Development are pleased to present Fordlandia, the first in a series on megalomania by British artist Dan Dubowitz. These photographs, completed in 2012, reveal what has become of Fordlandia, the American town built in the Brazilian rainforest by tycoon Henry Ford. This series comprises 13 new photographs of Henry Ford’s abandoned new town in the Amazon, set in the context of documentary photographs taken by Fordlandia staff in the 1930’s. The project reflects on Henry Ford’s delusions of grandeur at the time of the last great depression, and the precedent it established for industrialized consumption.

In 1927, seeking to sidestep the British rubber monopoly, Ford bought 2.5 million acres of rainforest on the Rio Tapajos deep in the Brazilian Amazon basin to establish a private source of rubber. 7,000 acres of forest were cleared while the head office in Michigan shipped in houses, a hospital, a school, a sawmill, a machine shop, and other facilities. The surrounding rainforest was burnt and cleared, and 2 million young rubber trees were planted.

Following Ford’s phenomenal success in modernizing industrial production and becoming one of the richest men in the world, he wanted to move on from the industry of building machines, to the industry of building men. Fordlandia was to be his ‘work of civilization’. It was a peculiarly personal and Fordist vision. Hammocks were banned, as was alcohol and other popular pleasures. There was a pioneering spirit too. To industrialize the jungle, things would need to be built, and beyond importing entire buildings, railways, fire hydrants, he imported raw materials and machines to make anything that might be needed. He was establishing his little America with his version of civilization, there were to be excellent schools and hospitals for all the work force and their families, and of course the dollar wage, which was a small fortune. But the high wages and enforced life style were counterproductive as the workforce returned to their home towns as soon as they had earned enough money.

Two riots exploded in the 1930s, one over working conditions, the second over lingering prejudice between Brazilians and the immigrant workers from Barbados. No sooner did the canopy of young rubber trees close overhead than Microcyclus ulei, a harmful rubber tree fungus, spread through the plantation, stripping the trees of their leaves. A plague of insects advanced from the forest, including legions of caterpillars. In 1945, after spending (in today’s terms) a third of a billion dollars on his dream of empire, and having failed to produce any rubber on a commercial scale, Ford’s son took over the business and in a matter of weeks gave Fordlandia to the Brazilian government for a pittance.

The precedents that Fordlandia helped establish have led to an onslaught on the rainforest: the colossal scale clearance of rainforest for hard woods, soya crops, grass for beef cattle and pollution caused by oil and gold mining. The rainforest has an important role in the global ecosystem and its immense biodiversity can only continue to be an infinite source of knowledge for climate, for medicines, for understanding plant and animal life – only if the Amazon is not viewed, as Ford did, as a resource for consumption.